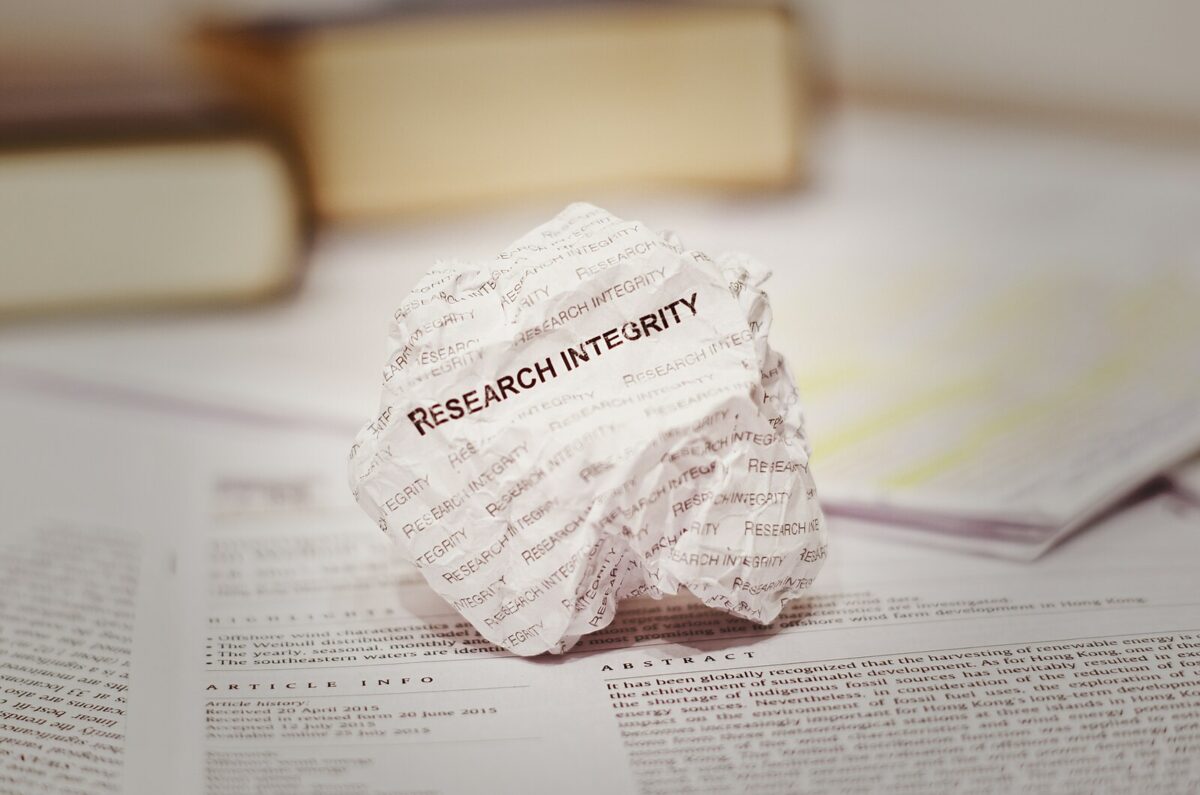

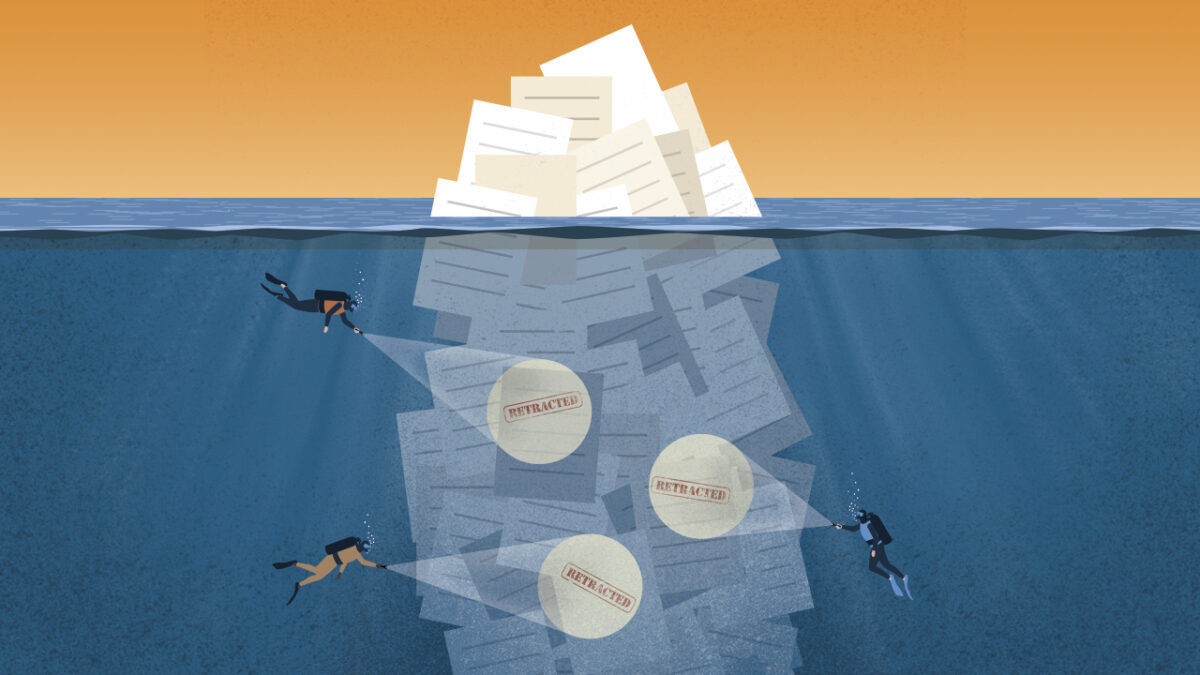

Research integrity extends beyond publication to include how scholarship is discovered, accessed, and used, and its societal impact depends on more than editorial practice alone. In practice, integrity and impact are shaped by a web of platforms and partnerships that determine how research actually travels beyond the press.

University press scholarship is generally produced with a clear public purpose, speaking to issues such as education, public health, social policy, culture, and environmental change, and often with the explicit aim of informing practice, policy, and public debate.

Whether that aim is realised increasingly depends on what happens to research once it leaves the publishing workflow. Discovery platforms, aggregators, library consortia, and technology providers all influence this journey. Choices about metadata, licensing terms, ranking criteria, or the use of AI-driven summarisation affect which research is surfaced, how it is presented, and who encounters it in the first place.

These choices can look technical or commercial on the surface, but they have real intellectual and social consequences. They shape how scholarship is understood and whether it can be trusted beyond core academic audiences. For university presses, this changes where responsibility sits. Editorial quality remains critical, but it is no longer the only consideration. Presses also have a stake in how their content is discovered, contextualised, and applied in wider knowledge ecosystems. Long-form and specialist research is particularly exposed here. When material is compressed or broken apart for speed and scale, nuance can easily be lost, even when the intentions behind the system are positive.

This is where partnerships start to matter in a very practical way. The conditions under which presses work with discovery services directly affect whether their scholarship remains identifiable, properly attributed, and anchored in its original context. For readers using research in teaching, healthcare, policy, or development settings, these signals are not decorative. They are essential to responsible use.

Zendy offers one example of how these partnerships can function differently. As a discovery and access platform serving researchers, clinicians, and policymakers in emerging and underserved markets, Zendy is built around extending reach without undermining trust. University press content is surfaced with clear attribution, structured metadata, and rights-respecting access models that preserve the integrity of the scholarly record.

Zendy works directly with publishers to agree how content is indexed, discovered, and, where appropriate, summarised. This gives presses visibility into and control over how their work appears in AI-supported discovery environments, while helping readers approach research with a clearer sense of scope, limitations, and authority.

From a societal impact perspective, this matters. Zendy’s strongest usage is concentrated in regions where access to trusted scholarship has long been uneven, including parts of Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. In these contexts, university press research is not being read simply for academic interest. It is used in classrooms, clinical settings, policy development, and capacity-building efforts, areas closely connected to the Sustainable Development Goals.

Governance really sits at the heart of this kind of model. Clear and shared expectations around metadata quality, content provenance, licensing boundaries, and the use of AI are what make the difference between systems that encourage genuine engagement and those that simply amplify visibility without depth. Metadata is not just a technical layer: it gives readers the cues they need to understand what they are reading, where it comes from, and how it should be interpreted.

AI-driven discovery and new access models create real opportunities to broaden the reach of university press publishing and to connect trusted scholarship with communities that would otherwise struggle to access it. But reach on its own does not equate to impact. When context and attribution are lost, the value of the research is diminished. Societal impact depends on whether work is understood and used with care, not simply on how widely it circulates.

For presses with a public-interest mission, active participation in partnerships like these is a way to carry their values into a more complex and fast-moving environment. As scholarship is increasingly routed through global, AI-powered discovery systems, questions of integrity, access, and societal relevance converge. Making progress on shared global challenges requires collaboration, shared responsibility, and deliberate choices about the infrastructures that connect research to the wider world. For university presses, this is not a departure from their mission, but a continuation of it, with partnerships playing an essential role.

FAQ

How do platforms and partnerships affect research integrity?

Discovery platforms, aggregators, and technology partners influence which research is surfaced, how it’s presented, and who can access it. Choices around metadata, licensing, and AI summarization directly impact understanding and trust.

Why are university press partnerships important?

Partnerships allow presses to maintain attribution, context, and control over their content in discovery systems, ensuring that research remains trustworthy and properly interpreted.

How does Zendy support presses and researchers?

Zendy works with publishers to surface research with clear attribution, structured metadata, and rights-respecting access, preserving integrity while extending reach to underserved regions.

For partnership inquiries, please contact:

Sara Crowley Vigneau

Partnership Relations Manager

Email: s.crowleyvigneau@zendy.io